My grandfather was gassed in the Somme not far from Villers-Bretonneux in August 1918.

It happened three months before armistice. The impact on my grandfather’s health was severe and lifelong, and resulted in his death thirty years later from the complications of nerve gas exposure.

I learned of my grandfather’s war service from my father just four years ago. The fondness in Dad’s voice when he spoke of his father – who died when Dad was 18 – touched me deeply. I don’t remember ever hearing much about my grandfather during my childhood, or maybe I just hadn’t been interested.

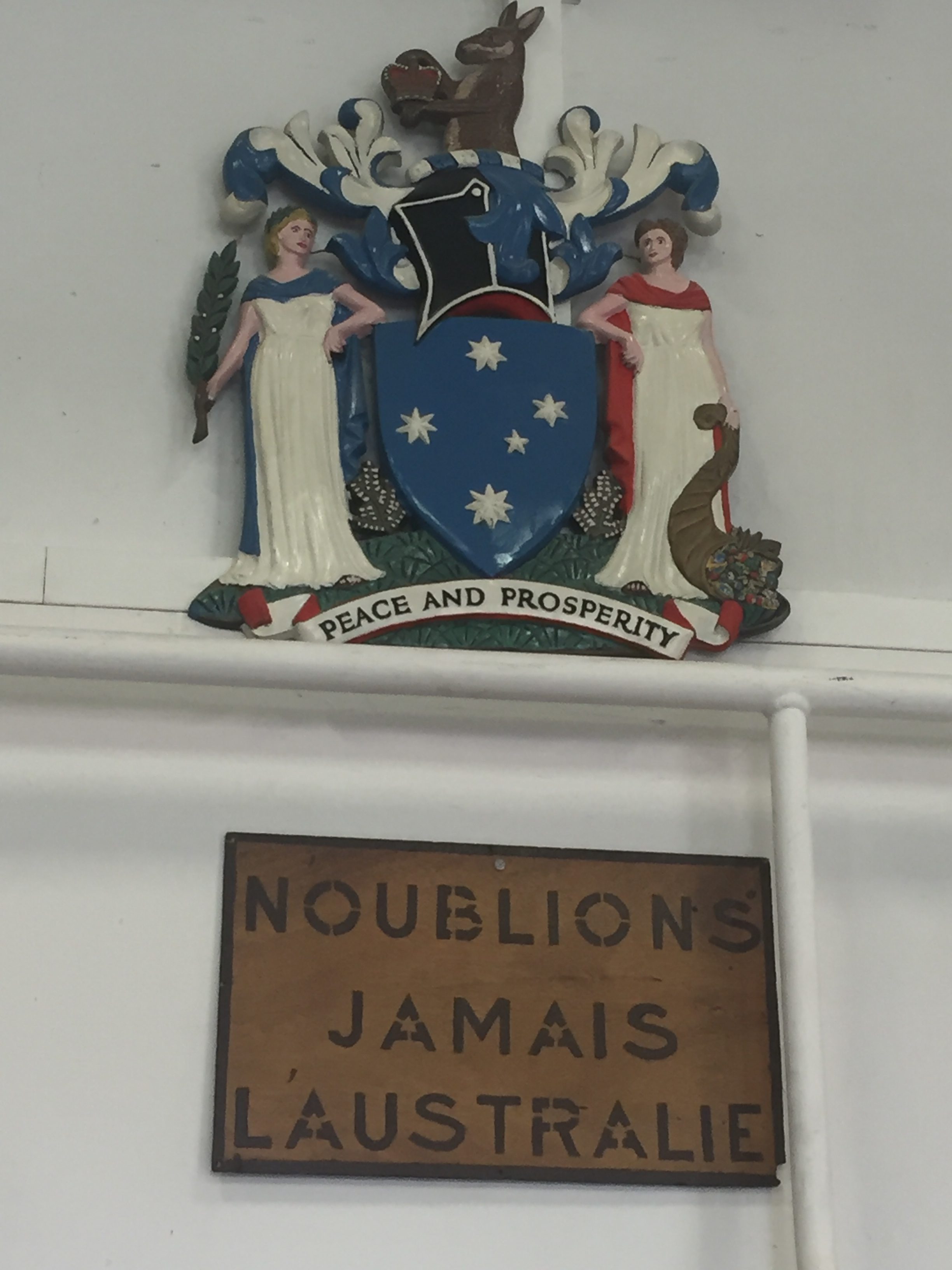

One Saturday in August 2015, I visited the Australian war memorial just outside Villers-Bretonneux. It was set amidst what were once the battlefields of the Somme. Despite it being the height of the tourist season, I was a lone visitor to this peaceful place of headstones and heartbreak.

The experience was a kind of awakening.

I had never given much thought to my stance on the commemoration of war. My British-born partner, an Australian resident since 1994, was both fascinated and disturbed by the hype around Anzac Day, and what he regarded as our obsession with the Anzac legend. I told him that we are a young country; that prior to WWI, Australian troops were considered part of the Commonwealth. We don’t look back on centuries-old battles like the British do; there are people alive today who are sons and daughters of veterans of WWI. For many Australians, this war and those that followed are personal.

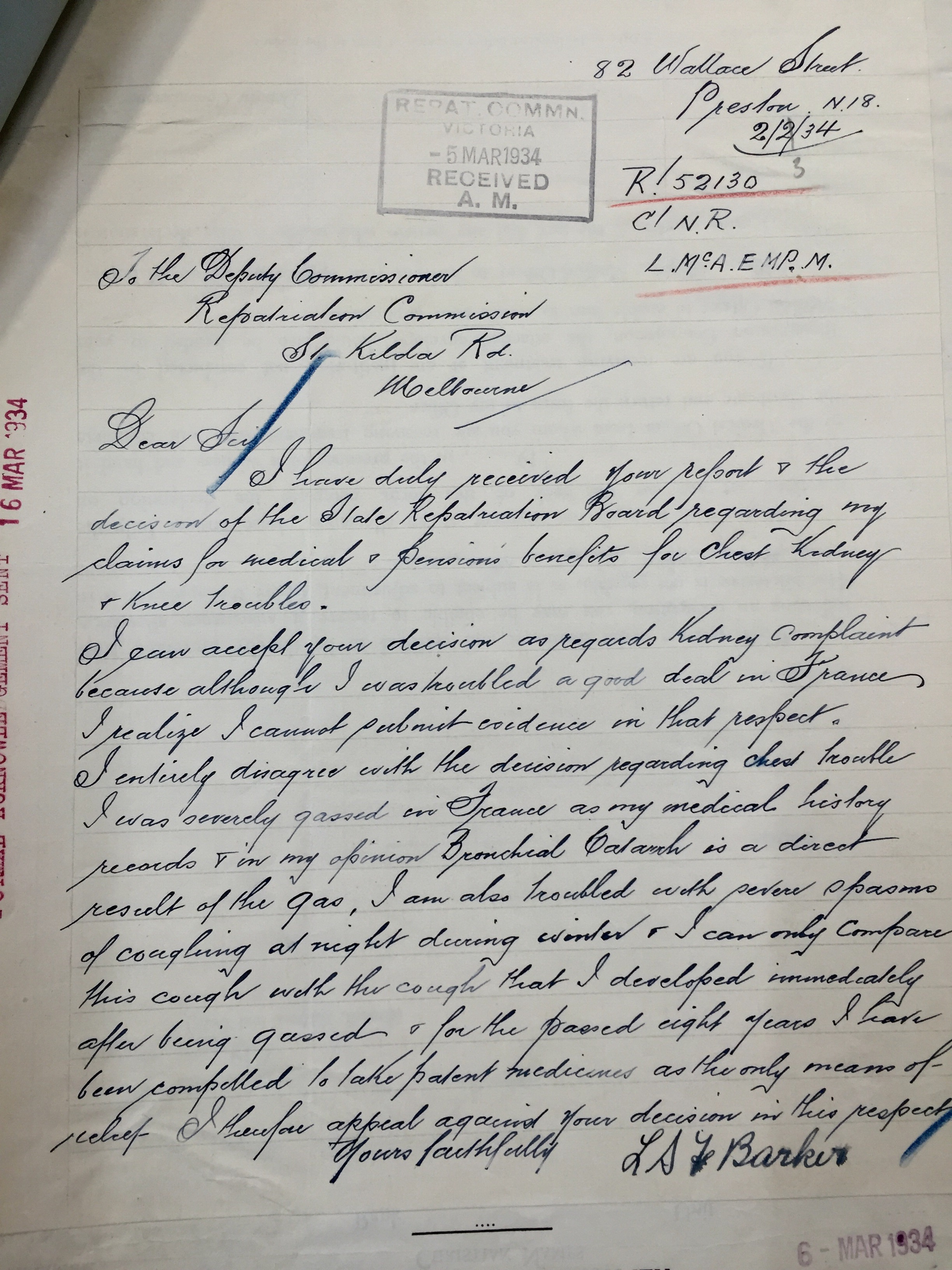

I became one of them that August day back in 2015. I got to know my grandfather a little better during my stay in France. Once back in Australia, I wrote to the National Archives requesting to see his war records. I saw his copperplate handwriting and read his respectful and repeated requests for a war service pension to help with ongoing medical bills. All his requests were refused.

I returned to the Australian war memorial at Villers-Bretonneux three years later.

April 25 2018 marked the centenary of the famous ‘Night of the Australians’. It was coincidentally the third anniversary of the original Anzac Day – when Australian troops were credited with single-handedly pushing the Germans out of Villers-Bretonneux. In a strange alignment of the stars, April 25 2018 also marked the first anniversary of my father’s death.

I was hoping to honour my father and his father, and to somehow work out a solution to my ongoing conflict about the commemoration of war. The signs weren’t hopeful. Anzac Day on the Somme dawned cold and comfortless. I had a sense of keeping watch throughout that long night; listening to the interminable platitudes of the pre-service speakers seemed like a kind of penance.

As dawn approached, so too did the dignitaries.

There followed wreath-laying, hands placed on hearts US-fashion and more platitudes. A motley collection of attention-loving pollies, a glimpse of Tony Abbott – proud mastermind of the just-opened Sir John Monash Commemorative Centre – and Prince Charles himself, emerging out of the pre-dawn darkness like a grey ghost.

French Prime Minister, Edouard Philippe, was the one ray of sunshine in an otherwise overcast and dismal dawn. He reiterated the message he had made the previous day at the launch of the Monash Centre. He spoke of the appalling conditions of life on the battlefields, and the inability of anyone not present at the time to ever truly imagine what conditions were like.

So we must tell them. We must show them. Again and again. Show the faces of these young men whose lives were snuffed out in the mud of the trenches.

Those faces had provided the most powerful images throughout the night and into the morning. They had been projected onto buildings in Amiens, the starting point of our pilgrimage to Villers-Bretonneux. They formed a sombre, silent tribute during breaks in the pre-dawn talk fest, far more compelling than any verbal tributes.

‘[We must] Show [the faces of these young men] with the help of modern technology.’ A reference to the inevitable high tech of the Monash Centre, whose eye-watering cost ($100 million) was a result of the perceived need for a sound-and-light ‘experience’ rather than a place of quiet contemplation.

And finally, tellingly, Edouard Philippe finished his speech with this admonition.

[Show it] Without taking our eyes off the names etched on to the memorial – names which are real, not virtual.

I took the prime minister’s advice and cancelled my booking for the Monash Centre the following day. I had no wish for a virtual WWI experience. The idea of using an app on my smart phone to deliver commentary on an interactive, digital display filled me with despair. Re-enactments, no matter how professional, set my teeth on edge. It seems I’m not alone, from the disappointing visitor numbers in the twelve months since its opening .

I prefer the reality – of the letters home, of the struggle to resume a normal life post-war, of the post-traumatic stress known then as shell shock. My grandfather suffered injuries as a 23-year-old on foreign soil – his first and only trip overseas – in the name of a government that refused to care for him on his return home. He built a life for himself after the war, fathering a son, building a small woodworking business that employed eight men, and making the best of things. That’s all the sound and light I need.

Thank you for your poignant and heartfelt writing.

A pleasure Margaret. It’s always lovely to receive feedback like yours.